The evolution of music

We all have a common sense of what music is. But why is it? Evolutionary biologists will tell you that various physical and cognitive capabilities evolved because they confer some adaptive advantage in the struggle for survival: Either prolonging life (finding prey and/or avoiding predators) and/or attracting a mate so that you can pass on genes. The first is referred to as natural selection and the second, sexual selection. The idea is that any advantage that comes from subtle variations in an organism’s genetic makeup is preserved in the species through procreation. Neither of these evolutionary drivers seem to be easily applied to music.

In this blog I want to review some of the main ideas about where music came from and why it has taken on the role(s) that it has in our daily lives. Along the way we will learn a little neuroscience and psychology. And while we are talking about neuroscience, in the next blog I will look more at the cognitive neuroscience and neurochemistry of how and why music affects us emotionally the way it does. But for now, let’s dive in and look deeper at some of the ideas about how and why music developed at all.

Back in the day, Darwin thought that music might be important in sexual selection in the same way that bird song and frog calls are important for those species. There is no question that the brain is to some extent, wired for music – young babies can appreciate musical form with little exposure or instruction and brain lesions at any age can eliminate some (or all) elements of musical capability. Music also appears to have been around for a goodly chunk of the time since the emergence of modern humans (homo sapiens) indicating that it’s probably characteristic of the species. But human music is quite different from the stereotyped calls of other species. By contrast, it’s not fixed in form or function but highly flexible in its characteristics and applications. The huge diversity of modern genres (Spotify identifies 1300) not to mention the range of music over the world’s different cultures and over the ages is obvious testament to that. This flexibility is called intentional transposability and it shares that characteristic with human speech.

The great evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould and his colleague Richard Lewontin argued back in 1979 that not every biological feature needed to arise as a consequence of selection but could arise as a consequence of other features which were selected for – a sort of “get it for free” idea.

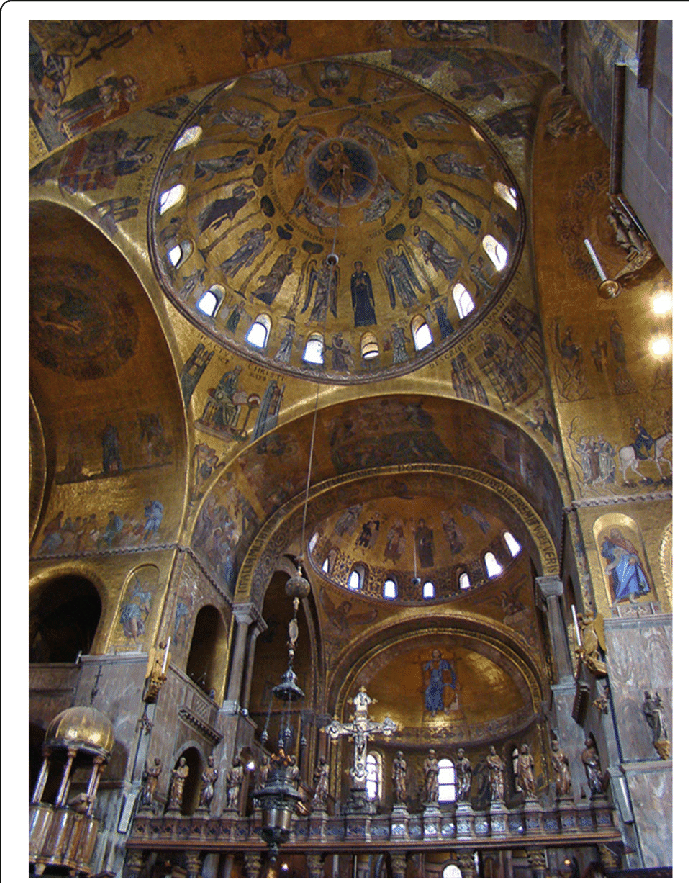

They called these things “spandrels” after the shape of two arches meeting in support of a dome in Byzantine and Renaissance church architecture – while spandrels add to the overall aesthetic of the building they simply arose out of the geometric necessity of the architectural plan. Not everyone has adopted the term but the idea persists and is also referred to as exaptation and many examples have been described (like feathers for warmth being deployed for flight etc.). I have very fond memories of sitting in a packed auditorium in the middle of a Sydney summer (without air conditioning) listening to Gould lecture on this – he was an amazing scientific orator!

So maybe music is a spandrel/exaptation and we enjoy this amazing faculty as a consequence of the development of other cognitive and brain functions. But before we take that tack, let’s look at some of the work that has been done about how music could convey an advantage to the species, if not directly to the individual organism!

Social and cultural context

Contemporary evolutionary biology is often seen in terms of the selfish gene (to use Richard Dawkins’ term) and about the survival of the individual organism in an environment that is “red in tooth and claw”. But this is not necessarily the most accurate or even a useful account of the human organism. Humans are a highly social species. Like other hominids (gorillas and chimpanzees etc.), humans live in groups and practice a range of behaviors that contribute to group cohesion. While it has been a long time since we have ritually picked the lice and nits off our neighbor to make them like us, Robin Dunbar (1996) has argued that, as hominid groups became larger, physical grooming was increasingly less practical. One solution would have been to connect using sound – a sort of vocal grooming. While early vocalization may have contributed to group harmony, the sounds themselves were probably not terribly meaningful in a semantic or symbolic sense. But this might have been a pressure for the selection of vocal capability. On this theme, David Huron (2001) argues that, from the available evidence, this points to a plausible origin for music (and speech) – a point that is reprised in his book “Sweet anticipation (2006)”.

There are strong reasons why humans favor group living – human babies are born very immature compared to many other species – i.e. they are altricial and require a long period of nurturing and protection if they are to mature to where they are able to pass on genes. The strength of bonding between the child and mother and other carers is critical to that survival. It takes a village to raise a child (or at least an extended family to raise many children) so the neurochemistry of bonding is firmly established in the human brain – Dopamine, Oxytocin, Serotonin and Endorphins. We will look at these in the context of music and emotion in more detail in the next blog but suffice to say here that many different human social interactions promote the release of these neurotransmitters. On release, neurotransmitters promote, among other things, pleasure, trust and other predispositions that enhance group bonding. So even before humans started to band together into larger groups, it is very likely that the bonding neurochemistry was strong. Of course, the brain was continuing to evolve (slowly) as was the vocal apparatus and its neural control systems, so it is likely that the range and capability of vocalization was evolving as well under the selective pressure of vocal grooming. Better vocal grooming could lead to larger cohesive groups which on balance, increased the individual’s chance of maturing and surviving.

Music, speech and the Theory of Mind

Clearly at some point in this evolution, music and speech took slightly different development paths but there are myriad studies of the cross linkages between these two functions – Aniruddh Patel provides a very detailed analysis of many of those connections in his book Music Language and the Brain (2010). One thing that is very clear, is that over the roughly 200 thousand years these capacities developed, it is extremely unlikely that this development occurred as a consequence of the accretion of many small genetic changes. Something big happened that produced a profound leap forward in the capacity of the human brain. Although the details are still not clear, at some point the human brain developed a sophisticated capacity that is referred to as Theory of Mind (ToM). Essentially, this is the capacity to recognize and analyze the mental and emotional state of others and to use that to interpret and predict their behavior. Over the last 2-3 decades, we have learned a lot about the emergence of ToM in the developing human from infant to adulthood. One powerful characteristic is the increasing capacity for abstraction and the manipulation of symbols that reflect aspects of the world and behaviors in it. Many have argued that this is a strong driver of language development and the development of higher order models of the world.

While it is very difficult to get a good understanding of human evolution over a couple of hundred thousand years, what we can say is that over that period there was an explosion of technical (advanced tools and buildings) and social (symbolic art) and cultural (social and religious organization) phenomena. It is inconceivable, in evolutionary terms, that these could be driven by the accretionary change in genes producing various mental modules that then enabled each of these developments – 200 thousand years is just a blink in evolutionary time! Whether ToM appeared de novo or is related to some more primitive precursor of the mammalian brain, is the subject of much research. The related brain areas have been dubbed the mentalizing network (see figure and review above) and located in the higher cortical areas characteristic of the hominids. With the maturation of ToM capabilities in humans, the brain created a cultural “ratchet” such that the success and discoveries of previous generations could be built upon by subsequent generations – firstly through oral and performed traditions and then with the invention of writing – recorded knowledge. Thus human cultural and intellectual development leaped ahead at a pace orders of magnitude greater than evolutionary development.

Connecting one mind to another

But what has this to do with music? Did it just come along for the ride or, as suggested above, were there other drivers that shaped the development of this faculty. In the human infant, as ToM matures, babies begin to understand that there are other minds out there – shared attention and mimicry, then vocal babbling and interactive play all begin to provide clues. Language is about connecting one mind to another mind and the emergence of common understanding through conversational interaction. The semantic elements in language convey information about object states and interactions which are important building blocks in decision making. But conversation is also about the non-verbal (multimodal) information made available through posture, facial expression, prosody, gaze etc. The signals passing between minds go well beyond the semantic information and include the affective or emotional context of the communication. This is important for two reasons. Firstly, conversation involves decision making and action (how to respond in the next conversation turn) and all decision making requires the engagement of emotional structures deep in the brain. Secondly, this stream of affective information also helps disambiguate the semantic stream by providing clues to the affective state of the conversant(s).

What this tells us is that “language” is actually a multimodal stream of information that conveys both semantic information and affective information. But there are other behaviours and capabilities that can also encode that affective information – the arts! In poetry and prose, spoken or written language is used principally for emotional impact but with music, dance, painting etc it is the multimodal and non-verbal aspects of the artefact that convey the affective information. That music can have a powerful emotional impact is indisputable from our own common experience and the growing body of neuroscientific knowledge documenting how the brain reacts to music. Music can convey the intimate emotions of the composer or the performer and shape the emotions of the listener or it might just predispose the listener to see the world around them in a particular way. Music also has the advantage that it can reach very large numbers of people simultaneously. Taking a cue from the idea of vocal grooming discussed above, music is eminently suitable for cultural and social events that involve the group. Music is used in social contexts to increase bonding, to orient the group to particular predispositions (music makes you braver), to provide collective relief or expression (such as grieving a loss).

From this perspective, as Bill Thompson and Steven Livingstone (2010) have observed, “music is merely one example of a broader biological function of affective engagement”. That is not to undersell the importance and impact of music but rather to contextualize it in a broader understanding of its significance for the brain and for society and culture. The development of ToM not only provided the insight that there are other minds like our own out there but also the capacity to abstract and create symbols that help understand what is going on out there. Musical instruments, musical forms, musical notation, musical recordings all added to the cultural ratchet that then set us on our musical journey. At this point in human history, as consumers and as creators, we are in the emotional embrace of many giants and, with the evolution of musical technologies over the last few decades, it is with sweet anticipation that we look towards tomorrow.

Really enjoying where you are going with this Simon. I’ve just started reading Drunk by Edward Slingerland. There are some interesting parallels between your thoughts on music and his on intoxicants.

I’m looking forward to your next post.

A really interesting article. Looking forward to the next one